4.5: Natural Monopoly Regulation

ECON 326 · Industrial Organization · Spring 2020

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/IOs20

IOs20.classes.ryansafner.com

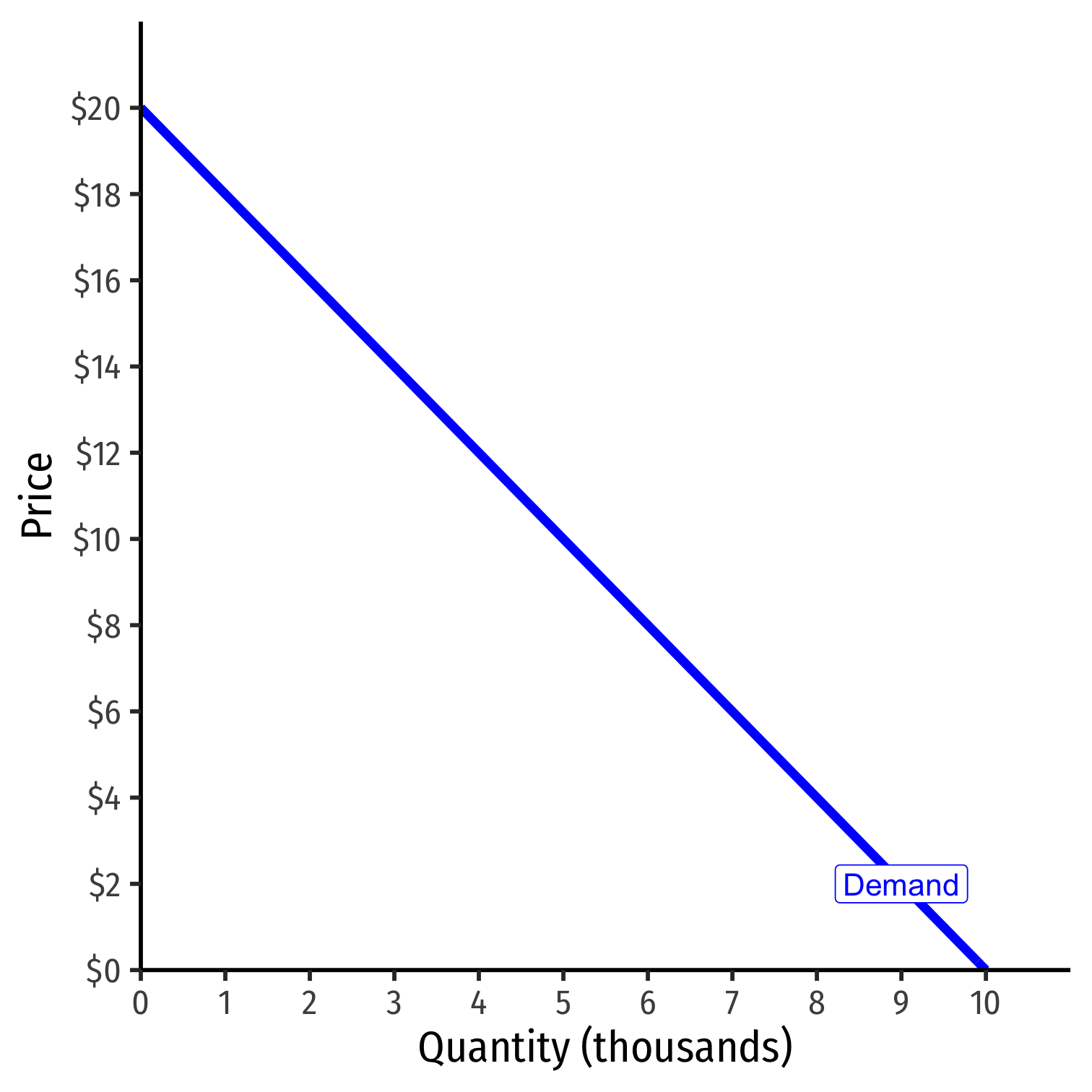

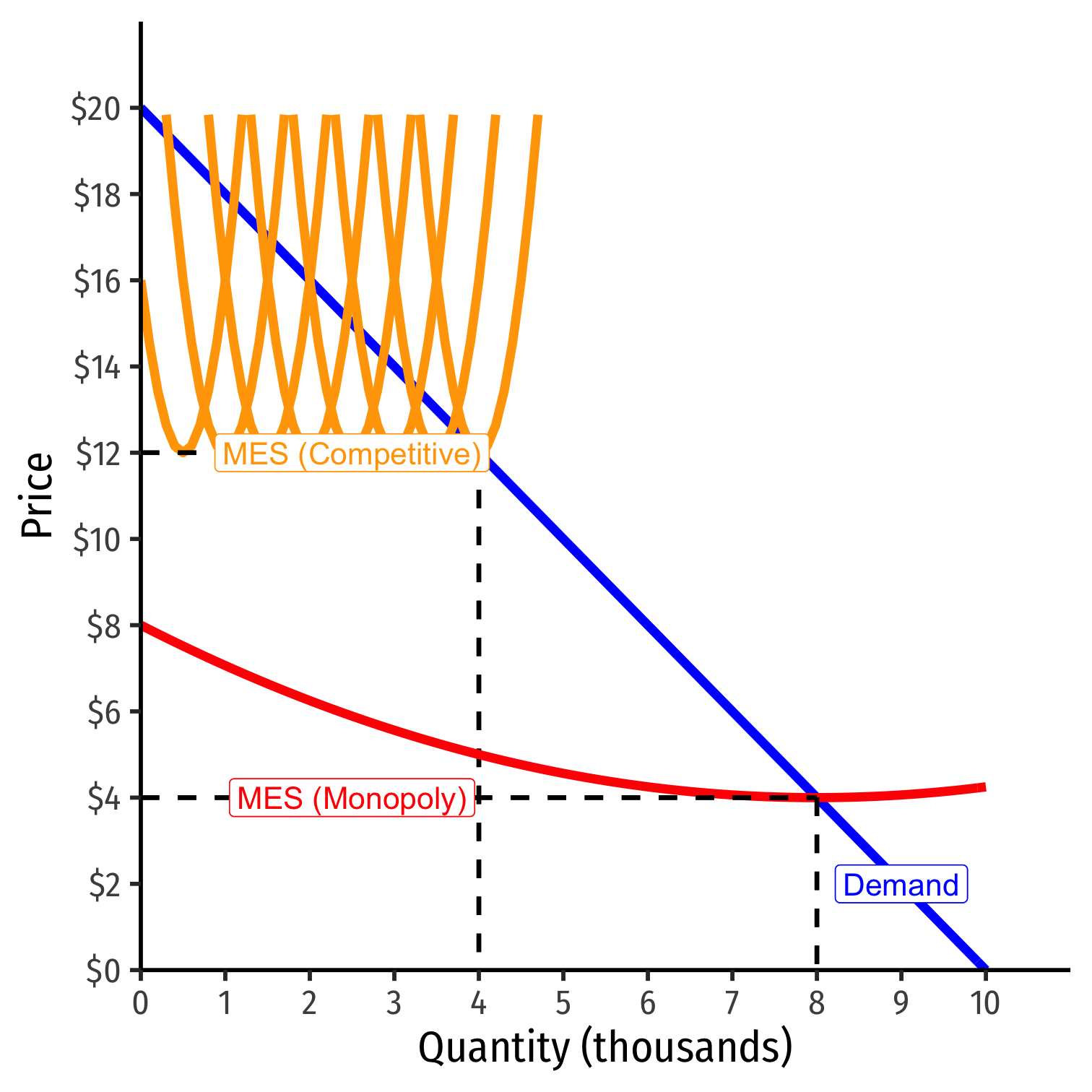

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

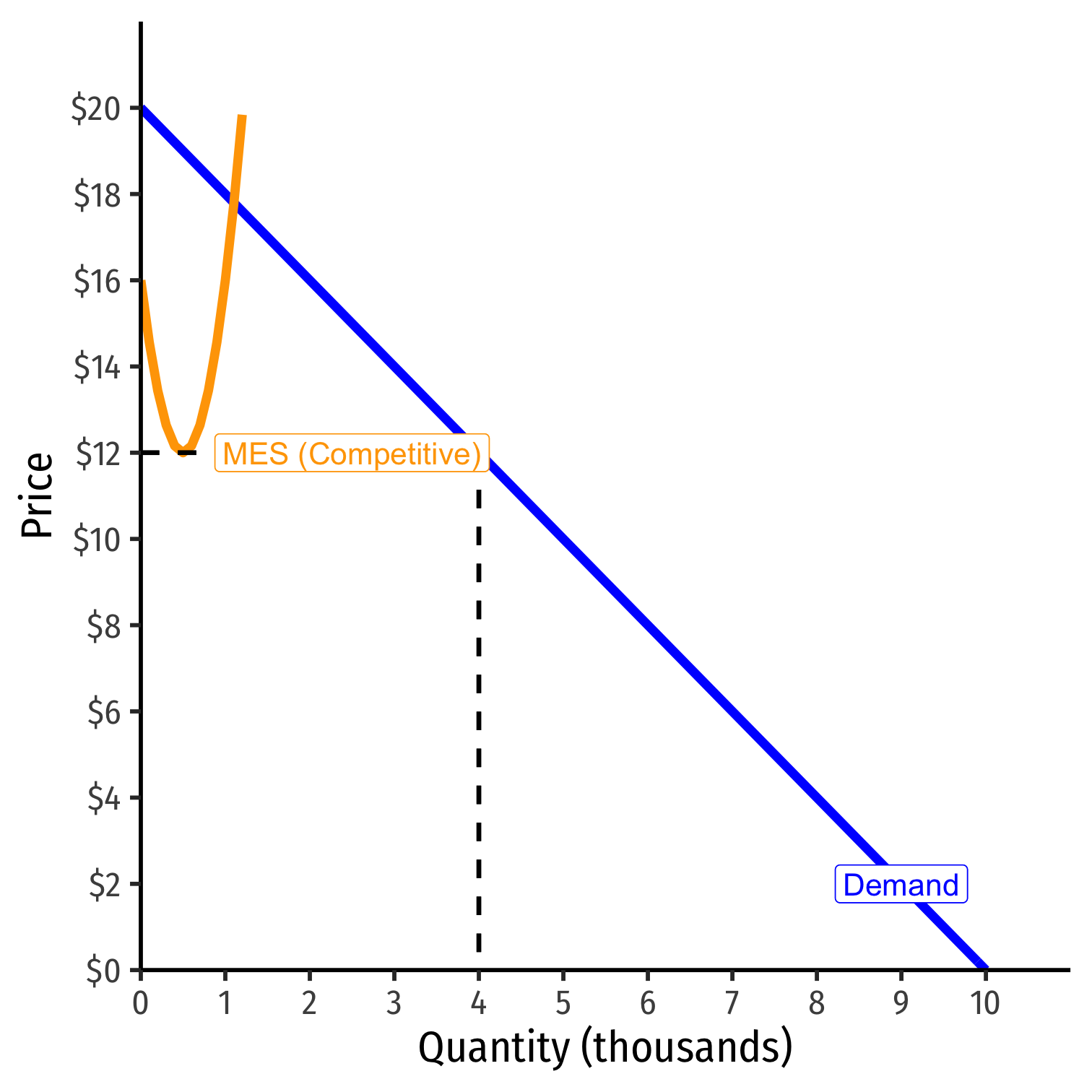

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

If MES is small relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during diseconomies of scale...

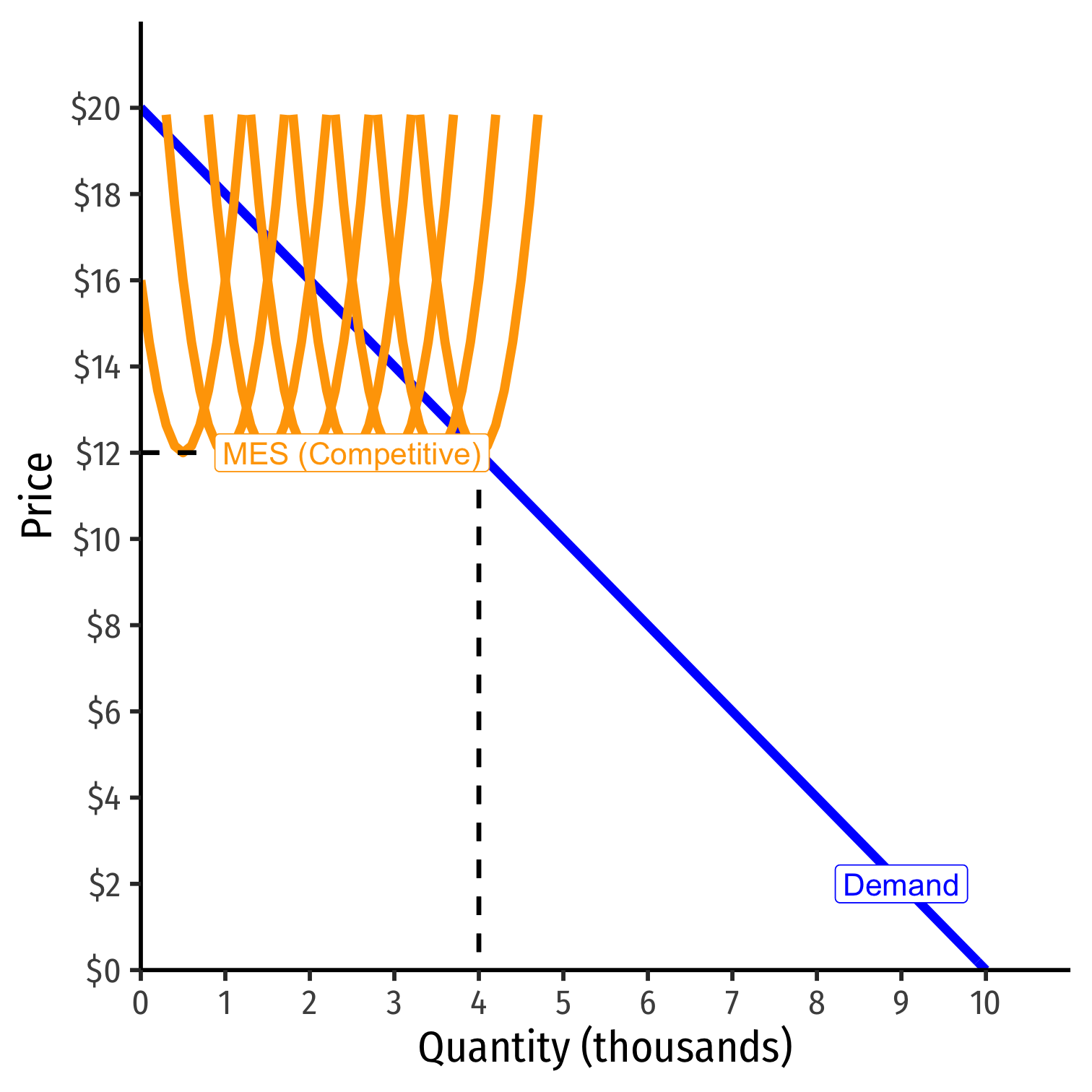

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

If MES is small relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during diseconomies of scale...

- ...can fit more identical firms into the industry!

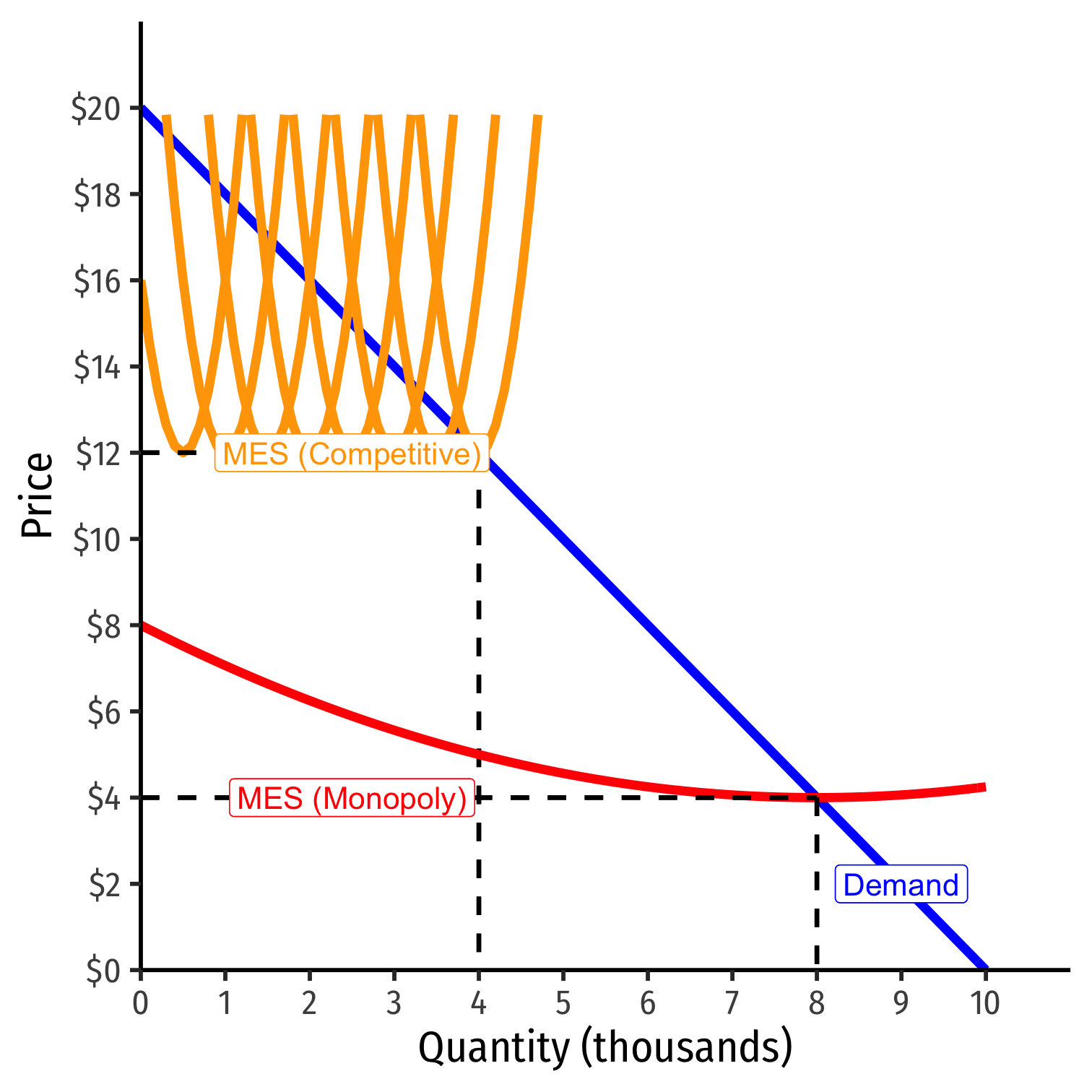

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

- If MES is large relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during economies of scale...

- likely to be a single firm in the industry!

Economies of Scale and Natural Monopoly I

If MES is large relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during economies of scale...

- likely to be a single firm in the industry!

A natural monopoly that can produce higher q∗ and lower p∗ than a competitive industry!

Natural Monopoly

![]()

Tend to have very high fixed costs, very low marginal costs (variable costs)

Implies a downward sloping average cost curve

Tend to be industries regulated as public utilities (gas, water, electric power) or common carriers (public transportation, telecommunications)

Natural Monopoly: Weak Case

Weak natural monopoly

p=AC at diseconomies of scale

Marginal cost pricing can be profitable and efficient

- Producing qc where p=MC, still above AC(q)

Natural Monopoly: Weak Case

This is an unsustainable natural monopoly: a second firm can profitably enter

Lowest price incumbent could break-even at is pAC

Entrant could profitably enter, produce qMES and charge a price between ACmin and pAC (incumbent's price)

Incumbent would lose (qMES) customers

Natural Monopoly: Strong Case

Strong natural monopoly

p=AC at economies of scale

Marginal cost pricing is not profitable

- Producing qc where p=MC, is below AC(q)

Natural Monopoly: Strong Case

A sustainable natural monopoly: a second firm cannot profitably enter

Lowest price incumbent could break-even at is pAC: Nash Equilibrium

- Entrant could not profitably enter

Regulating Natural Monopolies

Do We Need To Regulate Natural Monopoly?

Harold Demsetz

1930-2019

"If, because of production scale economies, it is less costly for one firm to produce a commodity in a given market than it is for two or more firms, then one firm will survive; if left unregulated, that firm will set price and output at monopoly levels; the price-output decision of that firm will be determined by profit maximizing behavior constrained only by the market demand for the commodity...The theory of natural monopoly is deficient for it fails to reveal the logical steps that carry it from scale economies in production to monopoly price in the market place," (p.56).

Do We Need To Regulate Natural Monopoly?

Harold Demsetz

1930-2019

"Why must the unregulated market outcome be monopoly price? The competitiveness of the bidding process depends very much on such things as the number of bidders, but there is no clear or necessary reason for production scale economies to decrease the number of bidders. Let prospective buyers call for bids to service their demands...There can be many bidders and the bid that wins will be the lowest. The existence of scale economies in the production of the service is irrelevant to a determination of the number of rival bidders. If the number of bidders is large or if, for other reasons, collusion among them is impractical, the contracted price can be very close to per-unit production cost," (p.57).

Do We Need To Regulate Natural Monopoly?

Harold Demsetz

1930-2019

If competition within the market is inefficient (natural monopoly), competition for the market (to be the sole producer) might be efficient

Franchise-bidding for public utilities:

- government can auction off a monopoly contract to the lowest bidder

- bids are price at which output is sold

Do We Need To Regulate Natural Monopoly?

Harold Demsetz

1930-2019

Replicates a perfectly contestable market:

- Nash equilibrium: lowest bidder sets p=MC or p=AC to drive π to 0

- Government can choose or randomize in the case of ties

Must make sure collusion is costly (or prevent it)

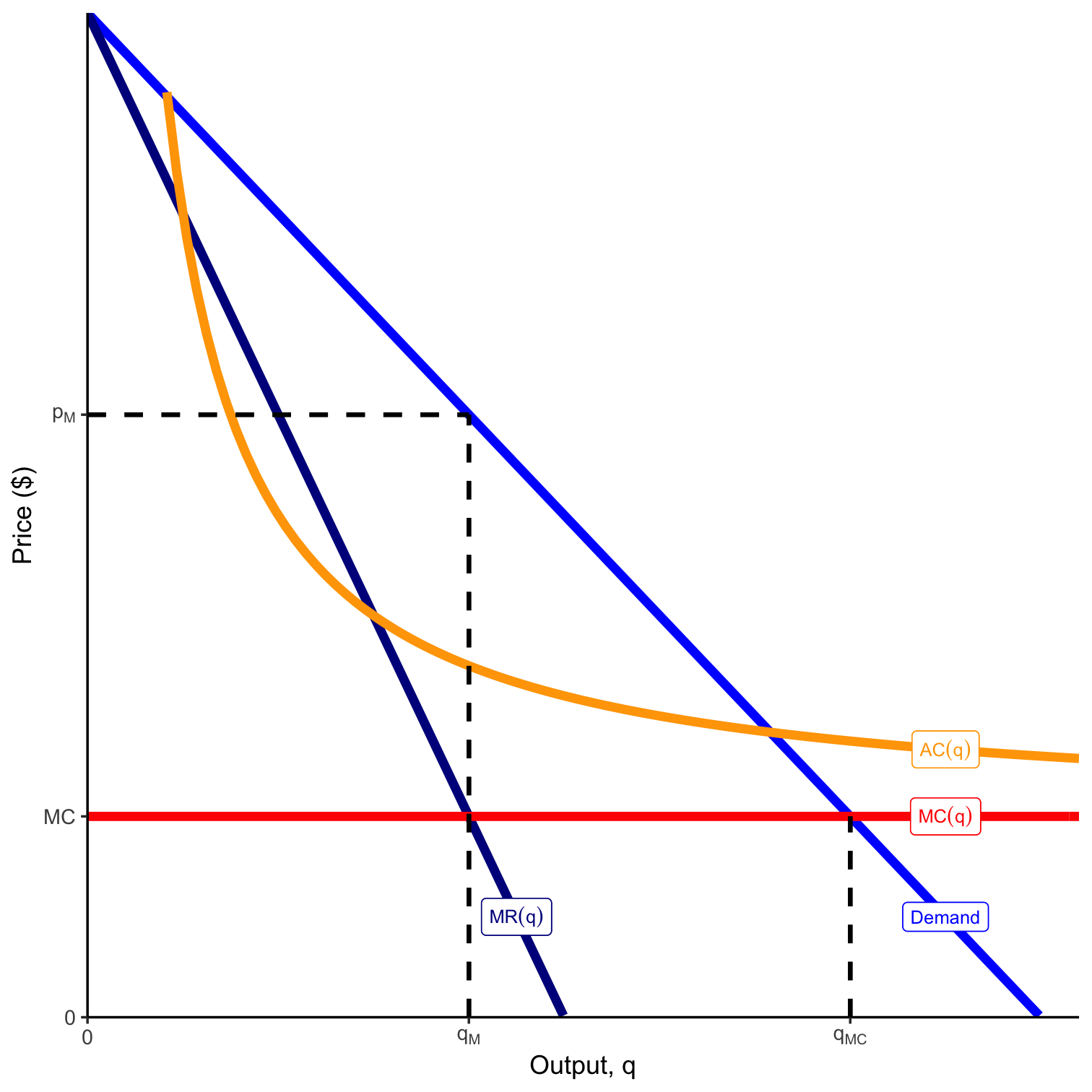

Price Regulation: Weak Case

Ignore franchise bidding possibility

Suppose government permits a single firm to be a natural monopoly

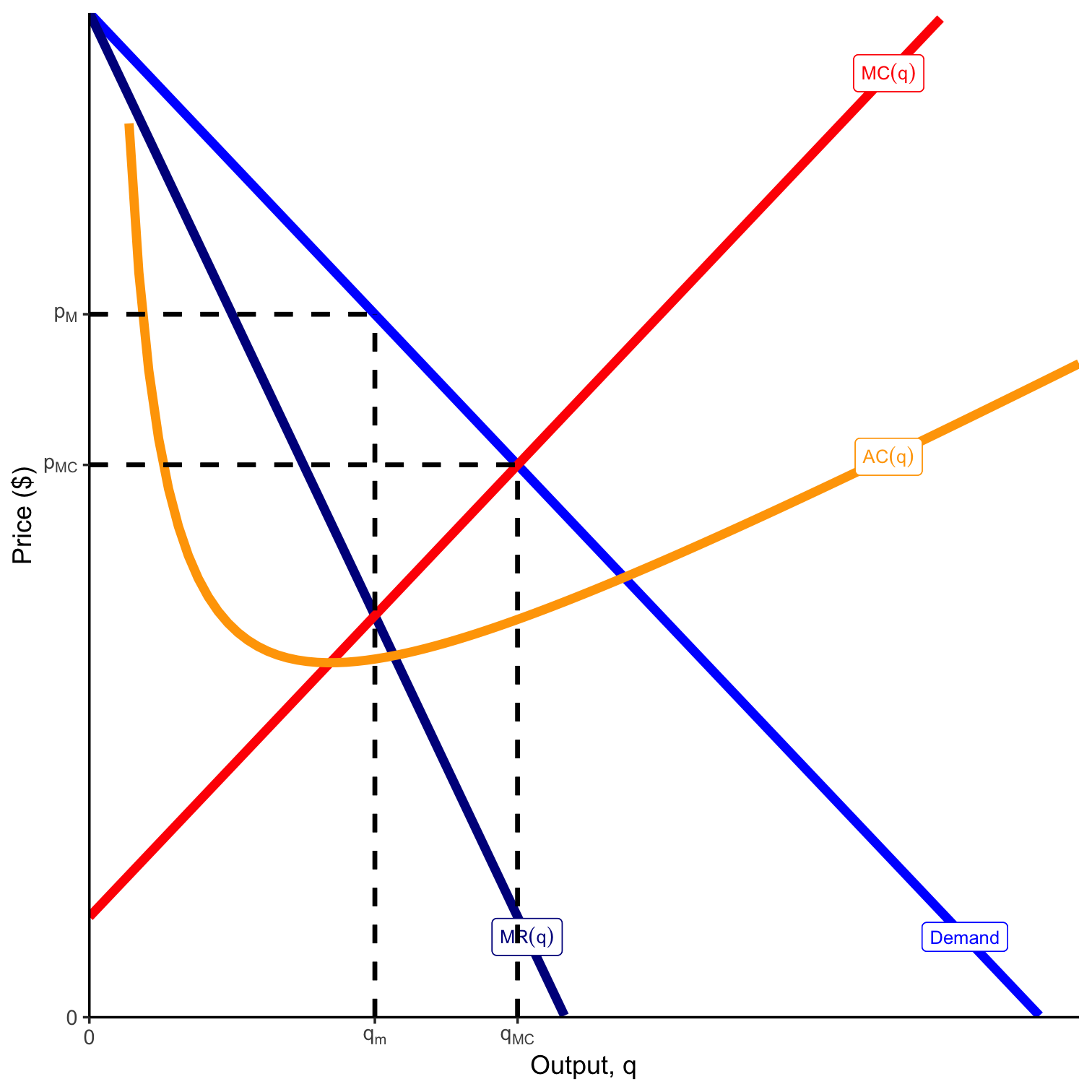

Price Regulation: Weak Case

If left to own devices, act like a monopoly

Restrict output to qM where MR=MC

Mark up price to consumers' max WTP: pM

- Small consumer surplus

- Earns profits

- Generates DWL

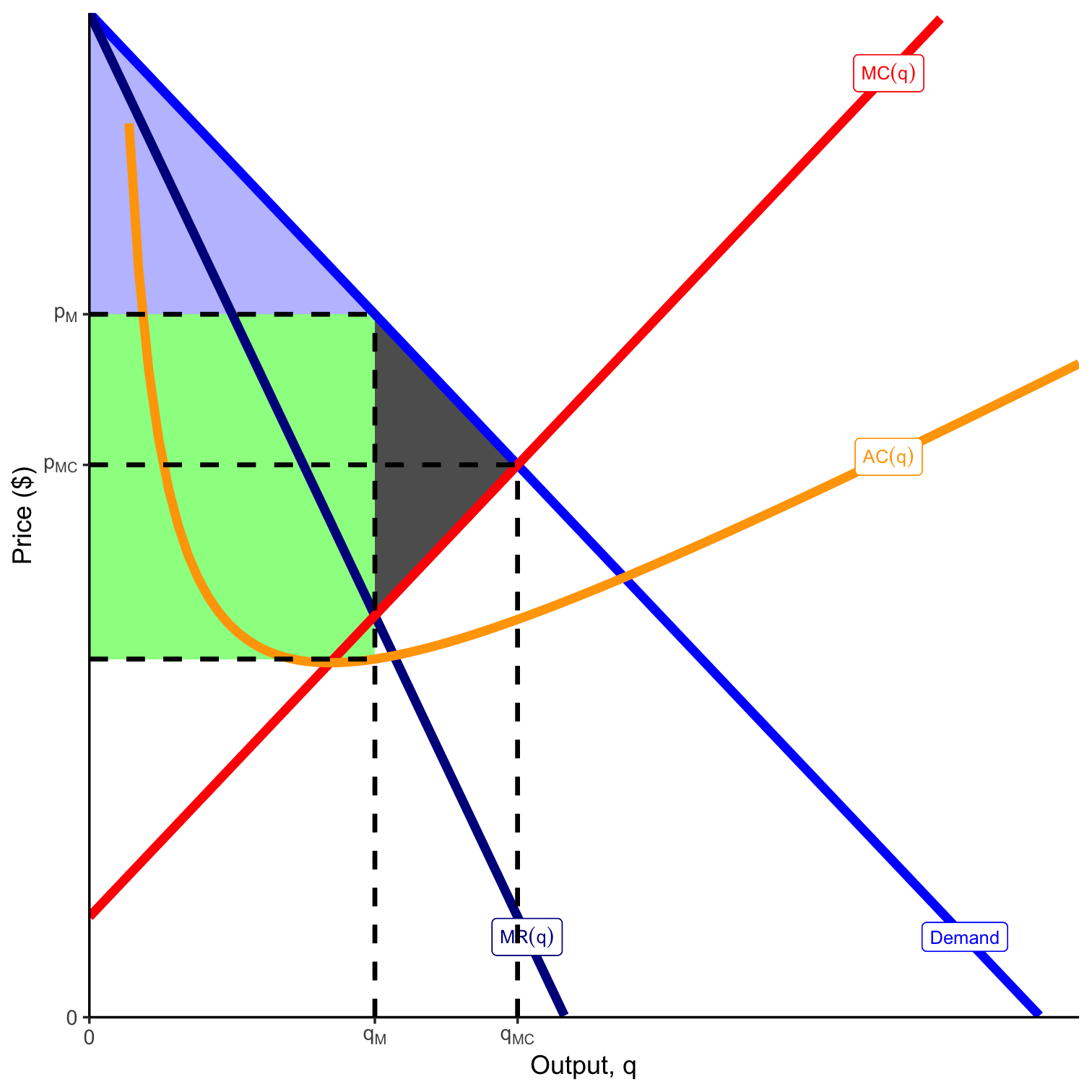

Price Regulation: Weak Case

Government can set price regulation

First best price: p=MC

- Possible in weak case, since AC<MC where p=MC

Allocatively efficient: p=MC

- No deadweight loss

- Monopolist even earns profits!

Would not be sustainable unless government protecting from entry

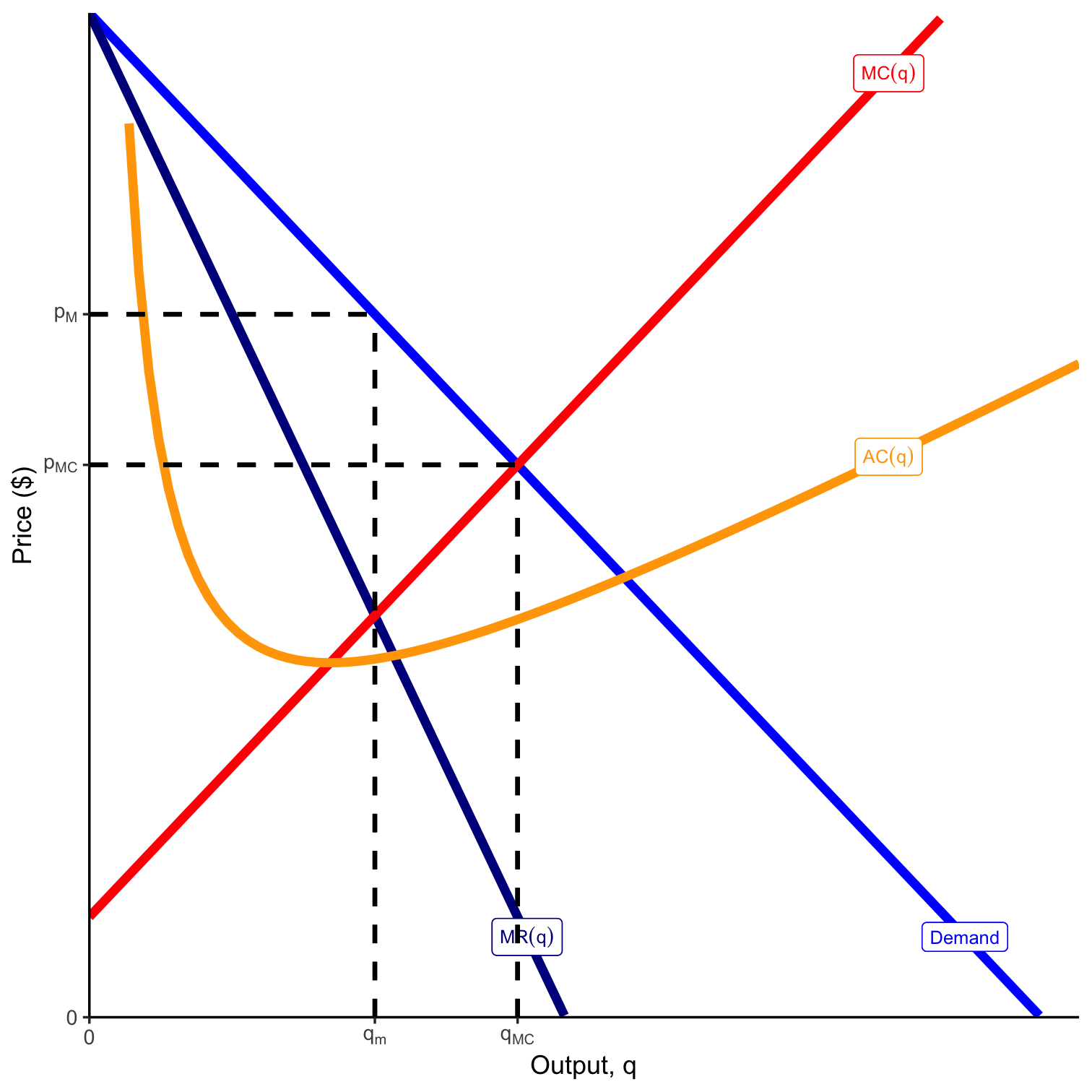

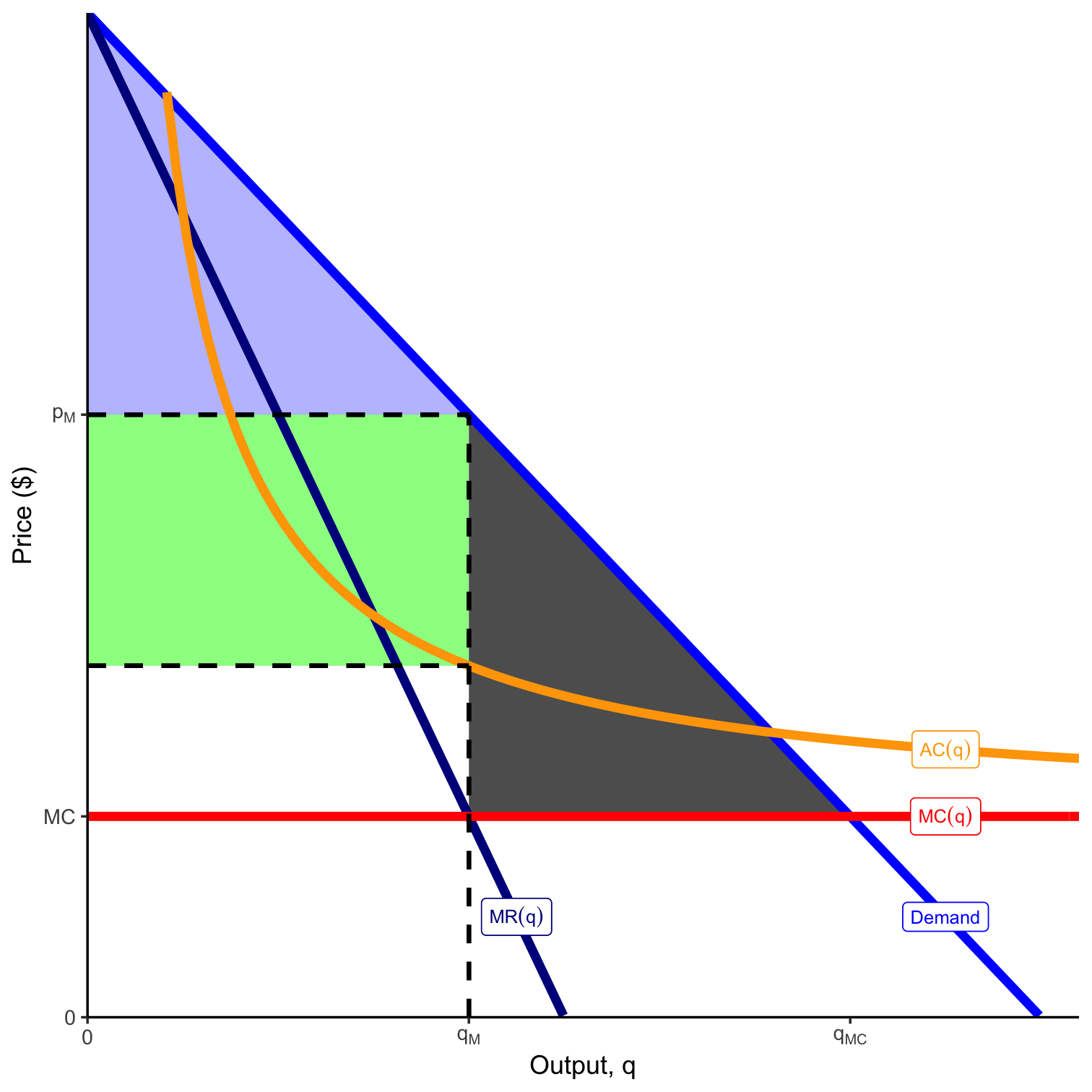

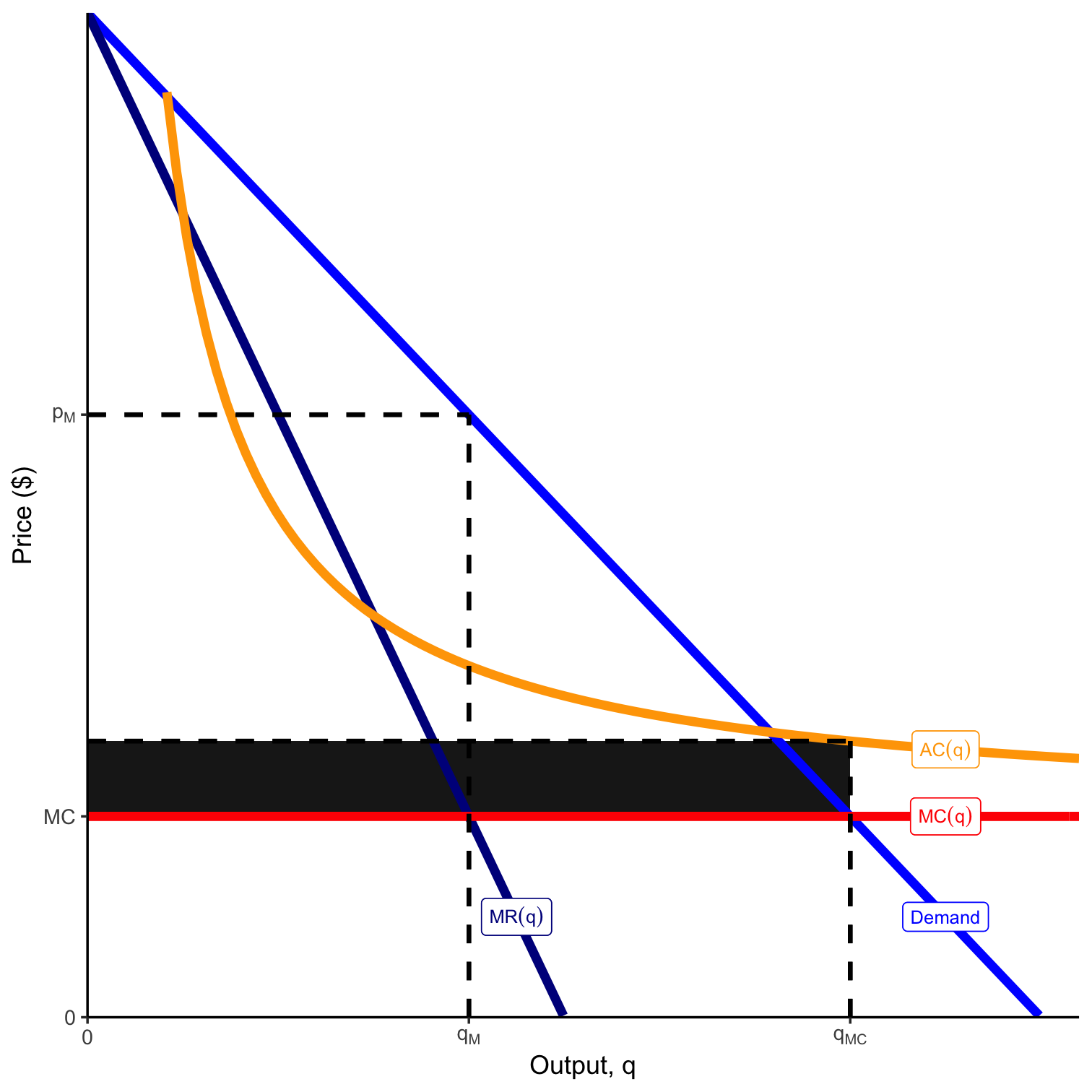

Price Regulation: Strong Case

If left to own devices, act like a monopoly

Restrict output to qM where MR=MC

Mark up price to consumers' max WTP at pM

- Small consumer surplus

- Earns profits

- Generates DWL

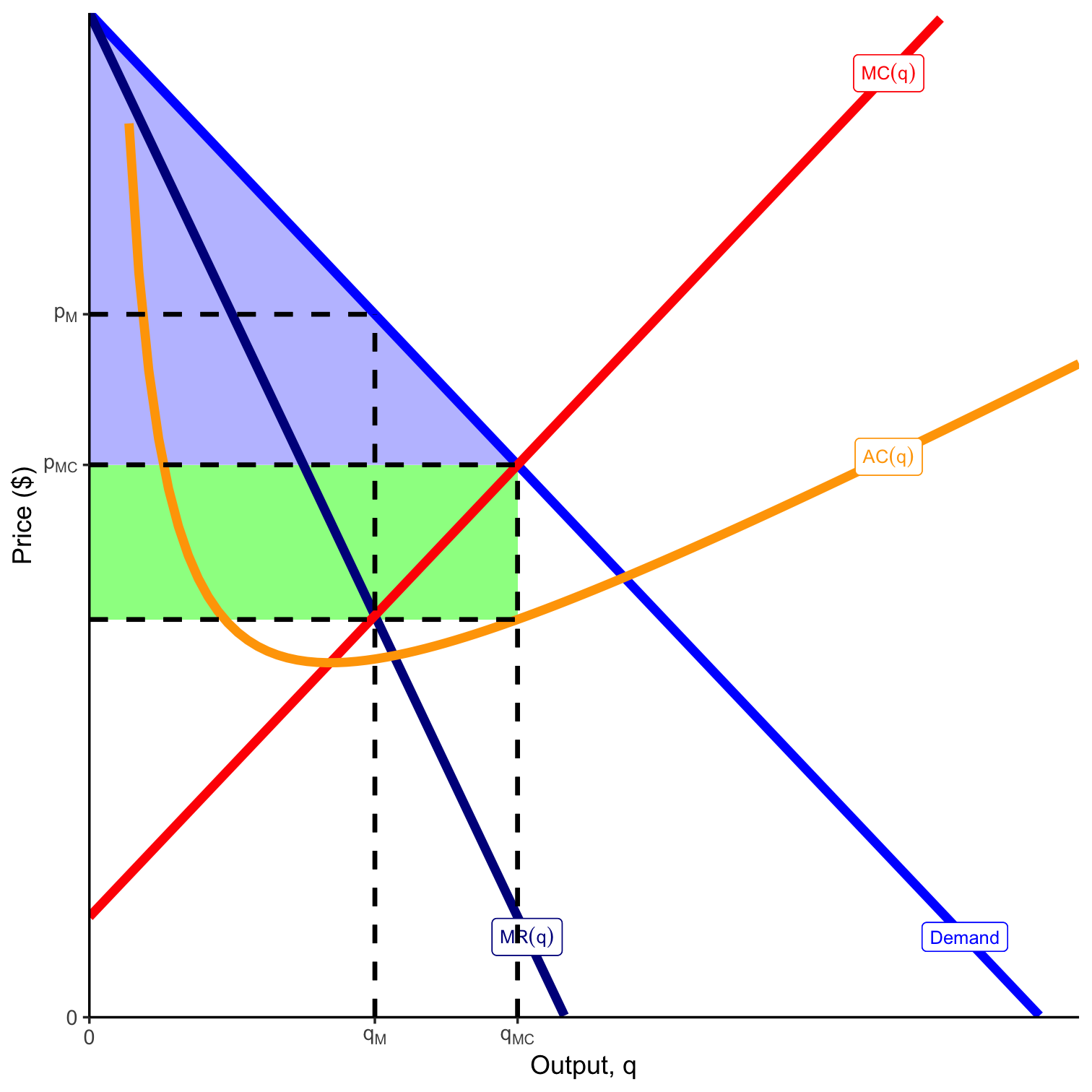

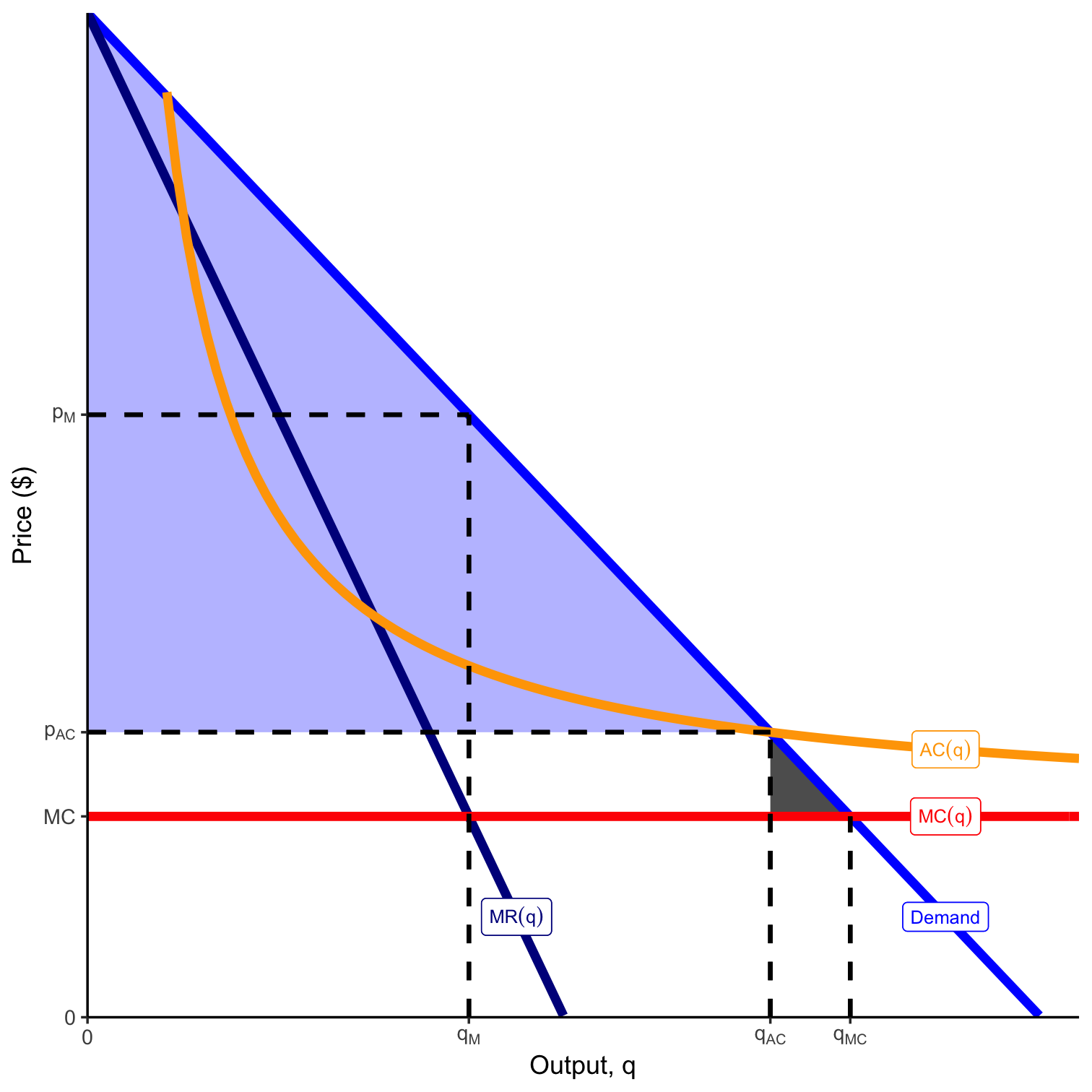

Price Regulation: Strong Case

Government can set price regulation

First best price: p=MC

- Unprofitable in strong case, since AC>MC where p=MC!

Government could provide a subsidy to monopolist (of size of losses at qMC)

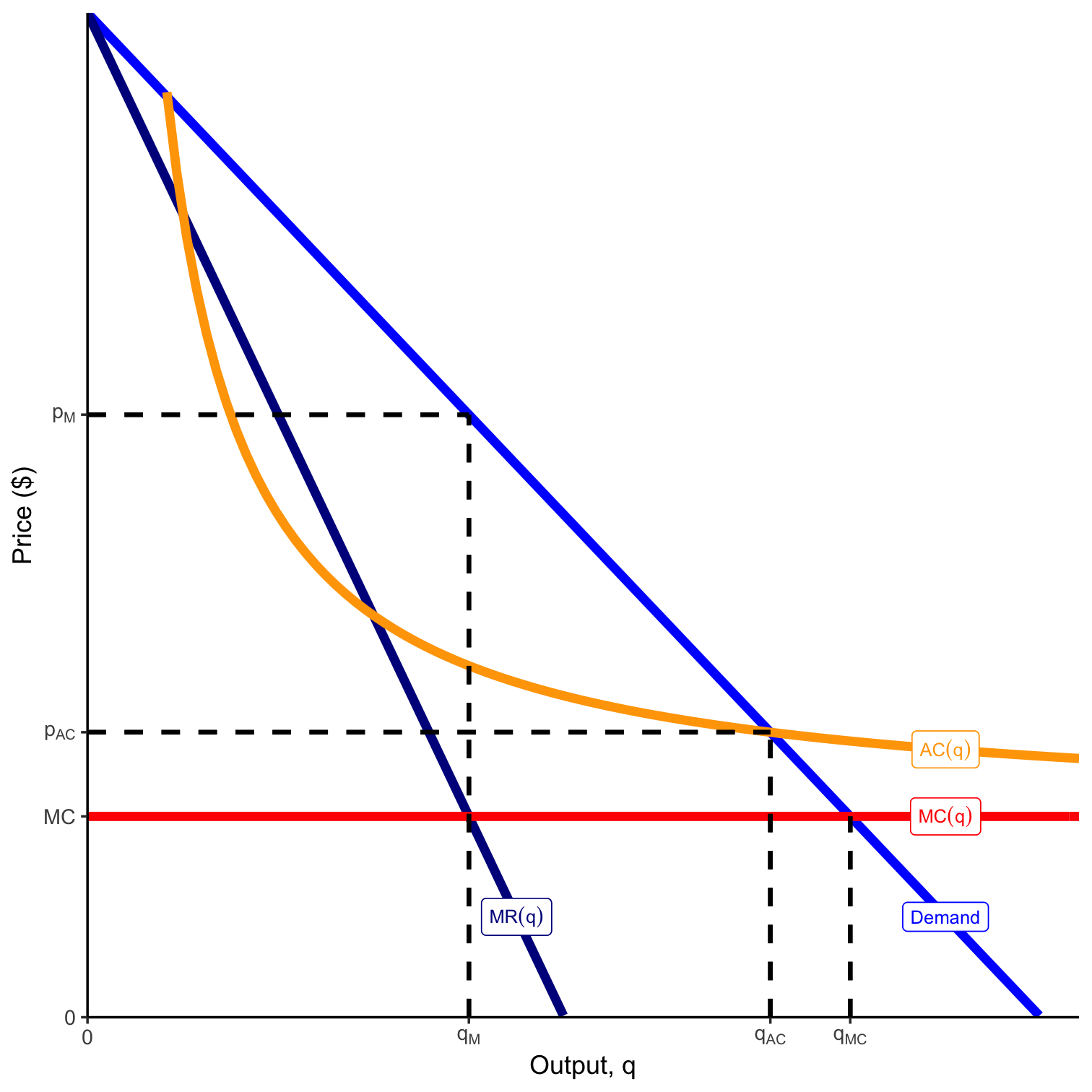

Price Regulation: Strong Case

Second best price: p=AC

- Allocatively inefficient (p>MC), some deadweight loss

- More consumer surplus

- No profit for monopoly

But, more incentive for monopolist than first-best marginal cost pricing

- At least breaks even

Price Regulation: Rate of Return Regulation

Rate of return regulation: government and monopoly agree to set a small p>AC to ensure some small profit

- "reasonable return on capital"

More incentive for monopolist to produce in this market

Price Regulation: Rate of Return Regulation

Rate of regulation is a type of "cost plus" regulation

- Monopolist reports its average cost, and government allows it to set a slightly higher price to generate small profit

Averch-Johnson effect or "gold plating": monopolist has incentive to overreport costs, overinvest in capital to raise its reported average costs (so government allows a price increase)

Averch, Harvey and Leland L Johnson, 1962, "Behavior of the Firm Under Regulatory Constraint," American Economic Review 52 (5): 1052–1069

Rationales for Regulation: Public Interest

Public interest rationale: regulation industries to benefit consumers, provide "common carriers"

- Lower prices, increase output, increase quality, prohibit price discrimination

Avoid "excessive duplication" from inefficient competition

Achieve allocative and productive efficiency

Rationales for Regulation: Rent-Seeking

George Stigler

1911-1991

Economics Nobel 1982

All groups desire to use the State to protect their interests (create a rent)

Direct subsidies boost profits but can induce entry into the industry

- dilutes profits/rents

Control of entry reduces competition and increases rents to incumbents

Olsonian problem: More organized industries fare better in controlling politics than less organized

Stigler, George J, (1971), "The Theory of Economic Regulation," Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 3:3-21

The Theory of Economic Regulation

George Stigler

1911-1991

Economics Nobel 1982

"[A]s a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefits," (p.3).

"[E]very industry or occupation that has enough political power to utilize the state will seek to control entry. In addition, the regulatory policy will ofeten be so fashioned as to retard the rate of growth of new firms," (p.5).

Stigler, George J, (1971), "The Theory of Economic Regulation," Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 3:3-21

Regulatory Capture

Regulatory capture: a regulatory body is "captured" by the very industry it is tasked with regulating

Industry members use agency to further their own interests

- Incentives for firms to design regulations to harm competitors

- Legislation & regulations written by lobbyists & industry-insiders

Regulatory Capture

Regulatory Capture

The Revolving Door

One major source of capture is the "revolving door" between the public and private sector

Legislators & regulators retire from politics to become highly paid consultants and lobbyists for the industry they had previously "regulated"

An Example: AT&T

The Telephone

1876: Alexander Graham Bell invents and patents the telephone

1877: Bell Telephone Company founded to manage Bell's patents

1889: Mergers create the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T)

The Bell System

"Bell System" of frachisees and associated companies managed by "Ma Bell", referred to generally as AT&T

Key divisions of AT&T

- AT&T Long Lines (long distance calling and interconnection of local exchanges)

- Western Electric (equipment manufacturing)

- Bell Labs (famous research & development)

- Bell operating companies (local telephone exchanges)

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"Most legislators, academics, and many othersbelieve the telephone industry is a natural monopoly that was privately monopolized by the aggressive actions of the American Telegraphand Telephone Company (AT&T). That was hardly the case. Although AT&T undoubtedly encouraged the monopolization of the industry,it was the actions of regulators and federal and state legislators that eventually led to the creation of a nationwide telephone monopoly," (p.267)

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"Specifically, three forces drove the monopolization process:

- The intentional elimination of what was considered wasteful or duplicative competition through exclusionary licensing policies, misguided interconnection edicts, protected monopoly status for dominant carriers, and guaranteed revenues for those regulated utilities;

- The mandated social policy of universal telephone entitlement, which implicitly called for a single provider to easily carry out regulatory orders; and;

- The regulation of rates (through rate averaging and cross-subsidization) to achieve the social policy objective of universal service. The combined effect of those policies was enough to kill telephone competition just as it was gaining momentum," (pp.267-268).

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"[T]elephone service traditionally has required laying an extensive cable network, constructing numerous call switching stations, and creating a variety of support services, before service could actually be initiated. Obviously, with such high entry costs, new firms can find it difficult to gain a toehold in the industry. Those problems are compounded by the fact that once a single firm overcomes the initial costs, their average cost of doing business drops rapidly relative to newcomers," (p.268)

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"Overlooked in the textbooks is the extent to which federal and state governmental actions throughout this century helped build the AT&T or 'Bell system' monopoly...Despite the popular belief that the telephone network is a natural monopoly, the AT&T monopoly survived until the 1980s not because of its naturalness but because of overt government policy...Once the government allowed this monopoly to develop with its assistance, AT&T's strength could not be matched by any competitor, resulting in a monopolistic market structure that survived well into the 1980's," (pp.268-269).

The Early History of AT&T

Thierer, Adam, 1994, "Unnatural Monopoly: Critical Moments in the Development of the Bell System Monopoly," Cato Journal 14(2): 267-285

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"Despite AT&T’s rapid rise to market dominance, independent competitors began springing up shortly after the original patents expired in 1893 and 1894. These competitors grew by servicing areas not served by the Bell System, but then quickly began invading AT&T’s turf, especially areas where Bell service was poor...By 1907, non-Bell firms continued to develop and were operating 51 percent of the telephone businesses in local markets. Prices were driven down as many urban subscribers were able to choose among competing providers...Whereas AT&T had earned an average return on investment of 46 percent in the late 1800s, by 1906 their return had dropped to 8 percent," (p.270).

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"After seventeen years of monopoly, the United States had a limited telephone system of 270,000 phones concentrated in the centers of the cities, with service generally unavailable in the outlying areas. After thirteen years of competition, the United States had an exten- sive system of six million telephones, almost evenly divided between Bell and the independents, with service available practically anywhere in the country," (p.271)

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"[CEO Theodore] Vail’s most important goals upon taking over AT&T were the elimination of competitors, the befriending of policymakers and regulators, and the expansion of telephone service to the general public...AT&T adopted a new corporate slogan as part of an extensive advertising campaign: “One Policy, One System, Universal Service" ... Vail began acquiring a number of independent telephone competitors, as well as telegraph giant Western Union. However, the government made it known quickly that such activity was suspect under existing antitrust statutes," (p.272).

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"Vail decided to enter an agreement that would appease governmental concerns while providing AT&T a firm grasp on the industry. On December 19, 1913, the “Kingsbury Commitment” was reached...the agreement outlined a plan whereby AT&T would sell off its $30 million in Western Union stock, agree not to acquire any other independent companies, and allow other competitors to interconnect with the Bell System...[and] require[d] that an equal number [of telelphones] be sold to an independent buyer for each system AT&T purchased...This provision allowed Bell and the independents to exchange telephones in order to give each other geographical monopolies. So long as only one company served a given geographical area there was little reason to expect price competition to take place...interconnection...eliminated the independents' incentive to establish a competitive long-distance system" (pp.272-273).

1913 Kingsbury Commitment

To avoid antitrust scrutiny (DOJ wanted to vertically break up AT&T):

AT&T would divest its control of Western Union and allow independent (non-Bell) companies to interconnect with AT&T's long distance network

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"Legislators began referring to competition in the same terms as Vail—'duplicative,' 'destructive,' and 'wasteful'...[The] prevailing [government] sentiment [was that], 'Competition resulted in duplication of investment.... The policy of the state was to eliminate this by eliminating as far as possible, duplication.' Many state regulatory agencies began refusing requests by telephone companies to construct new lines in areas already served by another carrier and continued to encourage monopoly swapping and consolidation in the name of 'efficient service'" ... "Vail chose at this time to put AT&T squarely behind government regulation, as the quid pro quo for avoiding competition. This was the only politically acceptable way for AT&T to monopolize telephony..." (p.274).

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"On August 1, 1918, in the midst of World War I, the federal government nationalized the entire telecommunications industry for national security reasons...The federal government...agreed to pay to AT&T 4.5 percent of the grossoperating revenues of the telephone companies as a service fee; to make provisions for depreciation and obsolescence at the high rate of 5.72 percent per plant; to make provision for the amortization of intangible capital; to disburse all interest and dividend requirements...Finally, AT&T was given the power to keep a constant watch on the government’s performance..." (p.275-276).

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"In addition, once the nationalized system was in place, AT&T wasted no time applying for immediate and sizable rate increases. High service connection charges were put into place for the first time. AT&T also began to realize it could use the backing of the federal government to coax state commissions into raising rates. In addition, once the nationalized system was in place, AT&T wasted no time applying for immediate and sizable rate increases. High service connection charges were put into place for the first time. AT&T also began to realize it could use the backing of the federal government to coax state commissions into raising rates...By January 21, 1919, just 5.5 months after nationalization, longd istance rates had increased by 20 percent," (p.276-276).

The Early History of AT&T

Adam Thierer

Adam Thierer

"During this period of government ownership, the decision was made to set standard long-distance rates throughout the country, based on average costs, In other words, subscribers calling from large cities would pay above costs in order to provide a subsidy to those in rural areas. So, early in the century cross-subsidization began, embraced by the industry...The intention of this action was obvious—Vail’s vision of a single, universal service provider was being adopted and implemented by the government through discriminatory rate structuring," (p.276-277).

1934 Telecommunications Act and FCC

1934 Telecommunications Act

Creates the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

"for the purpose of regulating interstate and foreign commerce in communication by wire and radio so as to make available, so far as possible, to all the people of the United States a rapid, efficient, Nation-wide, and world-wide wireand radio communication service with adequate facilities at reasonable charges."

1934 Telecommunications Act and FCC

FCC has power to restrict entry into the market

Competitors are required to obtain from FCC a "certificate of public convenience and necessity"

Avoid "wasteful duplication" and "unneeded competition"

Create and regulate common carriers for wireline (telephone, cable, later internet) and wireless (radio, later cellular)

United States v. AT&T

In 1970s FCC suspected AT&T was using monopoly profits from its Western Electric subsidiary to subsidize the costs of its network

DOJ brought a monopolization case against AT&T in 1972

United States v. AT&T

- 1982: AT&T and Government finalize a consent decree:

- Breakup of Bell system: AT&T's member telephone companies broke up into separate "Baby Bells" companies1

- AT&T keeps Western Electric, half of Bell Labs, and AT&T Long Distance

1 Most of which have since merged into Verizon, Sprint, and today's AT&T

Getting the Band Back Together