4.4: Antitrust III: Big Tech & Hipster Antitrust

ECON 326 · Industrial Organization · Spring 2020

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/IOs20

IOs20.classes.ryansafner.com

Antitrust III: Big Tech & Hipster Antitrust

Last class: The Paradox of Antitrust, Antitrust rent-seeking

Today:

Unique economics of platforms

- Network effect

- Multi-sided markets

Hipster Antitrust

- Kahn's critique of Amazon

- Antitrust issues in Big Tech

- Replacement of consumer welfare standard?

The Unique Economics of Platforms

Network Effects

Network Effect: the value of being on a particular network increases with the number of people already on the network (or expected to join)

A positive externality

Examples:

- Railroad track gauge

- Cellular networks (especially pre-2004)

- Bank & ATM networks

- Payment networks (Venmo, Square, etc.)

- Operating system (Android, Apple)

Network Effects

Metcalfe's Law: the number of connections on a network increases proportional to the square of the number of users connections=n(n−1)2

- n=2⟹1 connection

- n=5⟹10 connections

- n=12⟹66 connections

As limn→∞connections=n2

Path Dependence and Lock-In

Often a battle of standards

A Coordination Game

- Two Nash equilibria (A,A) and (B,B)

- Either just as good

- Coordination is most important

Path Dependence and Lock-In

Path Dependence: early choices may affect later ability to choose or switch

Lock-in: the switching cost of moving from one equilibrium to another becomes prohibitive

Inefficient Lock-In

Suppose we are currently in equilibrium (B,B)

Inefficient lock-in:

- Standard A is superior to B

- But too costly to switch from B to A

Alleged Example of Lock-In

David, Paul A, 1985, "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY," American Economic Review, 75(2):332-337

Alleged Example of Lock-In

Types of Lock-In

"First-degree" path dependency:

- Sensitivity to initial conditions

- But no inefficiency

Examples:

- language

- driving on left vs. right side of road

Liebowitz, Stan J and Stephen E Margolis, 1990, "The Fable of the Keys," Journal of Law and Economics, 33(1):1-25

Types of Lock-In

Later:

"Second-degree" path dependency:

- Sensitivity to initial conditions

- Imperfect information at time of choice

- Outcomes are regrettable ex post

Not inefficient: no better decision could have been made at the time

Liebowitz, Stan J and Stephen E Margolis, 1990, "The Fable of the Keys," Journal of Law and Economics, 33(1):1-25

Types of Lock-In

"Third-degree" path dependency:

- Sensitivity to initial conditions

- Worse choice made

- Avoidable mistake at the time

Inefficient lock-in

Liebowitz, Stan J and Stephen E Margolis, 1990, "The Fable of the Keys," Journal of Law and Economics, 33(1):1-25

Technological Choice and Uncertainty

Arthur, W. Brian, 1989, "Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events," Economic Journal 99(394): 116-131

In the long-run, Technology B is superior

But in the short-run, Technology A has higher payoffs

Inefficient lock-in

But what about uncertainty?

- What set of institutions will choose best under uncertainty?

Technological Choice and Uncertainty

Arthur, W. Brian, 1989, "Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events," Economic Journal 99(394): 116-131

Role for entrepreneurial judgment and "championing" a standard

- Someone who "owns" a standard has strong incentive to see it adopted

Champions who forecast higher long-term payoffs can subsidize adoption in the short run

Platforms

Platforms

A multi-sided market or a "platform" is a managed marketplace where an intermediary matches together two different groups of users to exchange

- Platform itself is often a business, helping to match users together across groups for a fee

Simple example: newspapers

- Group A: readers

- Group B: advertisers

Platforms

The Digital Disruption is Here

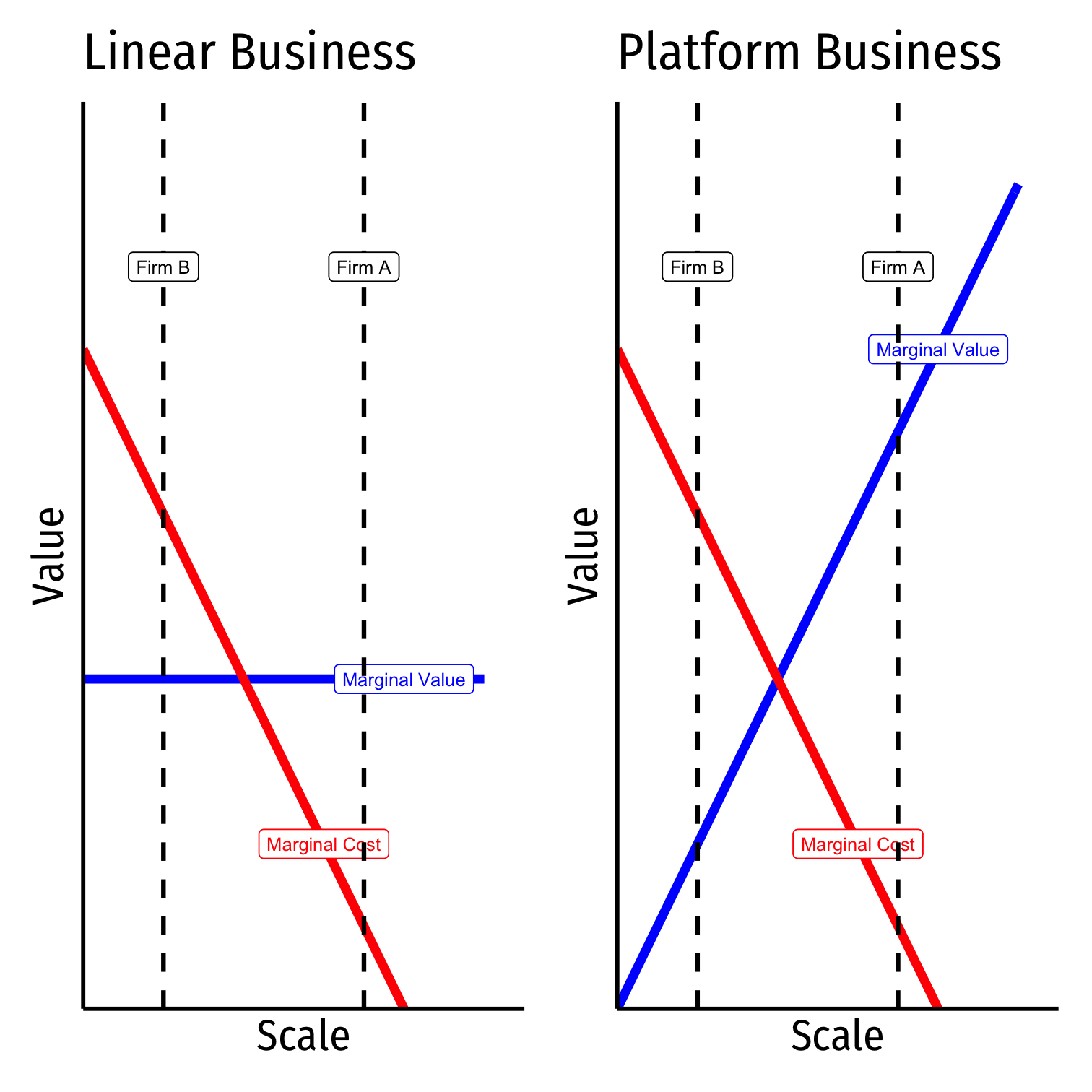

Non-Platform Business Models

Linear business model: serve one segment of the market

- direct to consumers or business (next-stage of supply chain)

Owns one side of the transaction

Products have an inherent value

Compete in one dimension: on cost via economies of scale

Platform Business Model

Platform business model: facilitate transactions between multiple groups

- "be the market"

Owns infrastructure that adds value to both sides of the transaction

Platform Business Model

- Compete in multiple dimensions:

- on cost via economies of scale (high entry barriers)

- on customers via network effect

- may also provide features to either/both groups

Platform Business Model

Competition between platforms is often "winner-take-all"

Large initial costs and low initial value

Increasing value due to network effect

High barriers to entry to compete with existing platform

- trust, history, reputation, volume, size of network

Platform Examples

Moazed, Alex and Nicholas L. Johnson, 2016, Modern Monopolies: What it Takes to Dominate the 21st Century Economy

Matchmaking

The Long Tail of Transactions

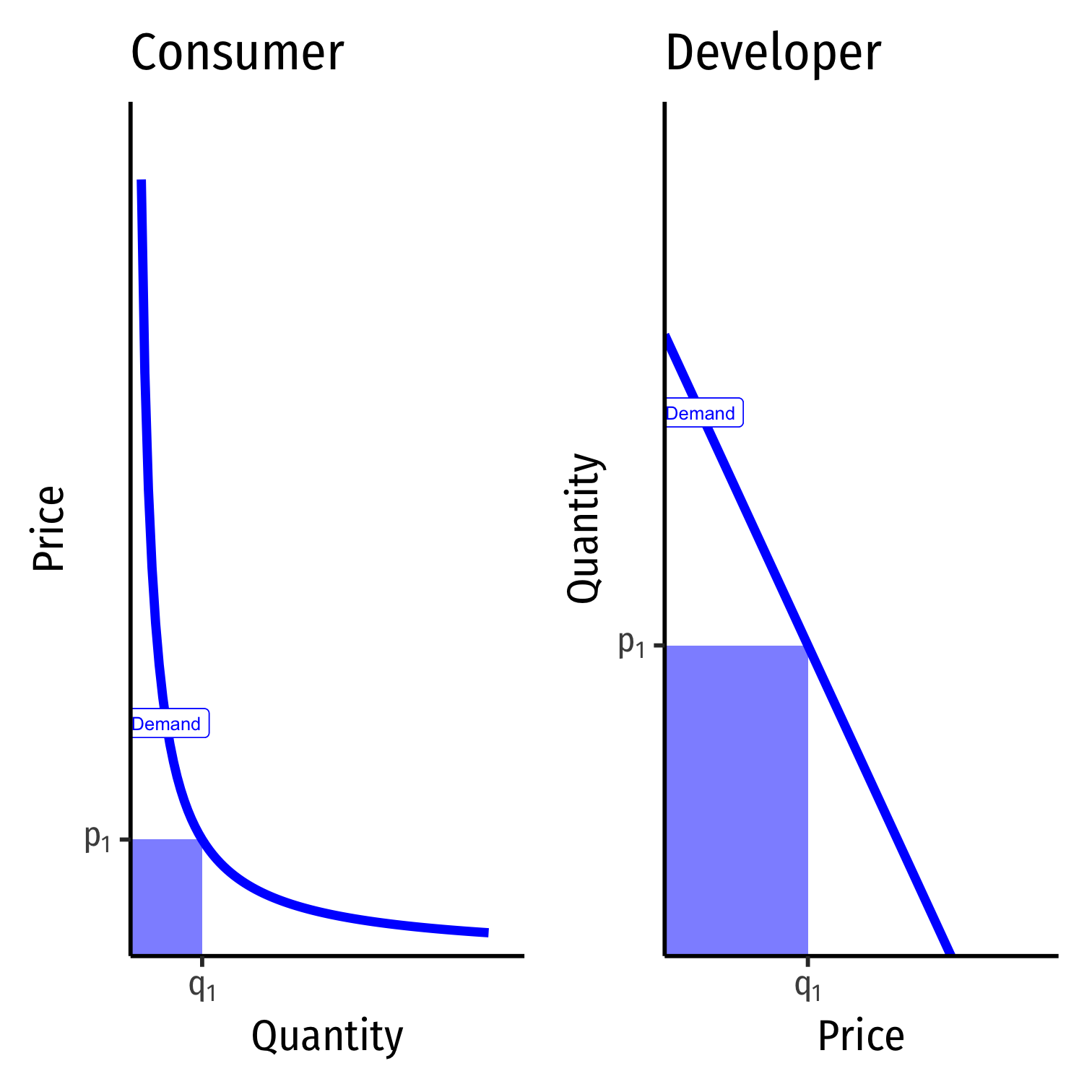

Pricing for Platforms

- Traditional business pricing model: price each market to maximize revenue

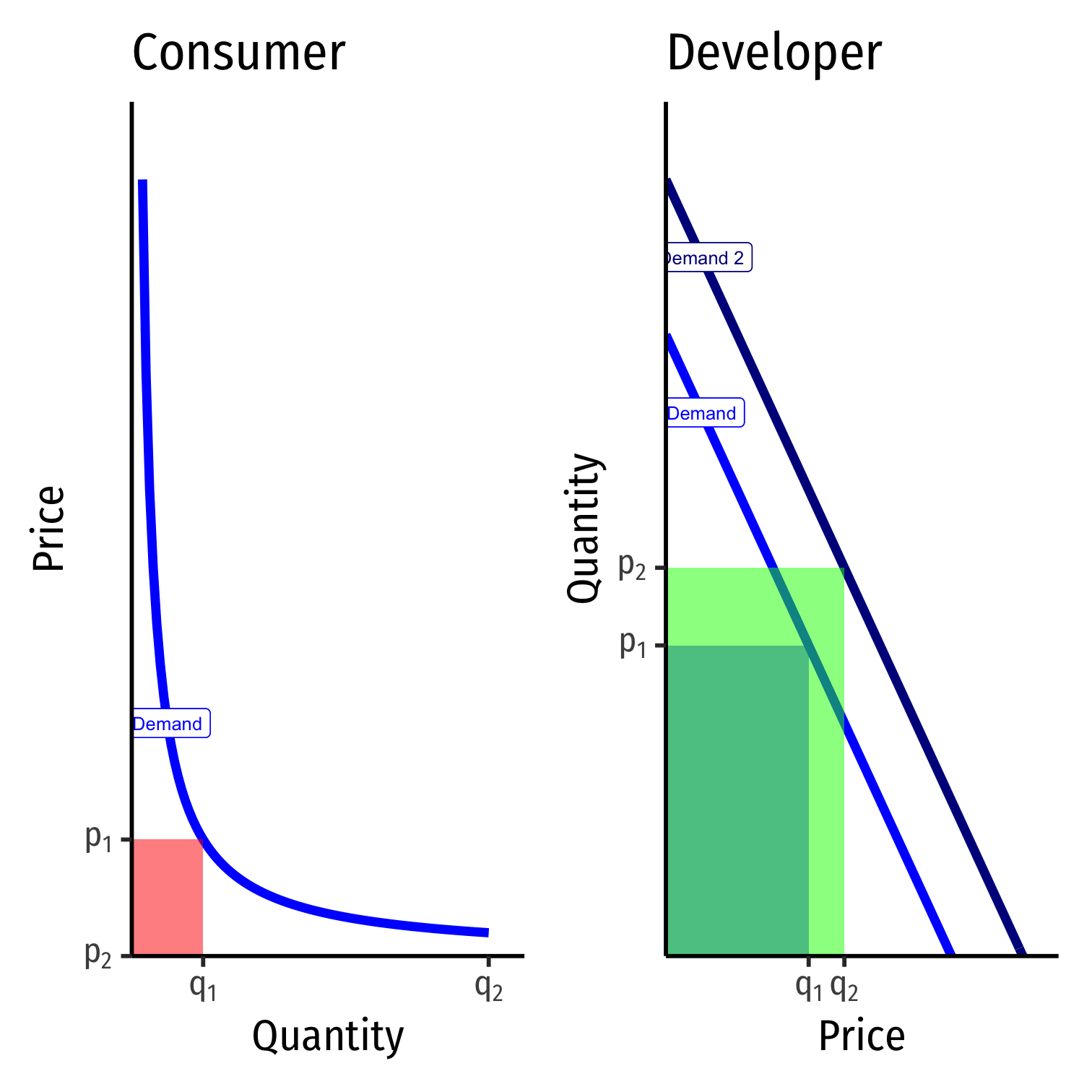

Pricing for Platforms

Traditional business pricing model: price each market to maximize revenue

Platform business: so long as revenue lost from Consumers < revenue gained from Developers: cross-subsidize

- Lower price on Consumers (even to 0) to boost demand

- Increases demand for Developers, raise price on them

Standard "champion" forecasting future value: subsidize early adopters!

The "Subsidy Side" and the "Money Side"

Evans, David S and Richard Schmalensee, 2016, *Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms

Rise of Platforms in S&P 500

Hipster Antitrust

Hipster Antitrust

Lina Khan

1989-

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox" Yale Law Journal 126(3)

Response to Bork's Antitrust Paradox and the dominant "consumer welfare standard"

- Antitrust should only be about consumer welfare, not small-business protectionism

- Focus only on classic market power behavior: high price, low output, low quality

Amazon (and other platforms) have fiercely low prices and provides enormous consumer surplus

Hipster Antitrust & Big Tech

Most dominant tech companies are platforms with large market share

But consider consumer welfare standard and focus on price

These platforms offer very low prices (often $0!), high quantity, high quality, and ample choice to consumers

- Consumers are often "paying" in their data, sold to advertisers

What about the producers' (advertisers, sellers, etc) side of the market?

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox"

Lina Khan

1989-

"Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a retailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and expand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e-commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny," (p.710).

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox"

Lina Khan

1989-

"This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competition to 'consumer welfare,' defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the architecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive," (p.710).

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox"

Lina Khan

1989-

"These concerns are heightened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have rewarded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. Second, because online platforms serve as critical intermediaries, integrating across business lines positions these platforms to control the essential infrastructure on which their rivals depend. This dual role also enables a platform to exploit information collected on companies using its services to undermine them as competitors," (p.710).

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox"

Lina Khan

1989-

"The dominant framework in antitrust today fails to recognize the risk that Amazon's dominance poses for discrimination and barriers to new entry. In part, this is because—as with the framework's view of predatory pricing—the primary harm that registers within the 'consumer welfare' frame is higher consumer prices. On the Chicago School’s account, Amazon’s vertical integration would only be harmful if and when it chooses to use its dominance in delivery and retail to hike fees to consumers. Amazon has already raised Prime prices. But antitrust enforcers should be equally concerned about the fact that Amazon increasingly controls the infrastructure of online commerce—and the ways in which it is harnessing this dominance to expand and advantage its new business ventures," (p.780).

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox"

Lina Khan

1989-

"The conflicts of interest that arise from Amazon both competing with merchants and delivering their wares pose a hazard to competition, particularly in light of Amazon’s entrenched position as an online platform. Amazon’s conflicts of interest tarnish the neutrality of the competitive process. The thousands of retailers and independent businesses that must ride Amazon’s rails to reach market are increasingly dependent on their biggest competitor," (p.780).

Amazon Exerting Market Power on its Platform?

What's The Difference?

Amazon: Possible Solutions

Investigate Amazon's business practices

Break apart Amazon's brand (Amazonbasics) from Amazon's marketplace platform

Is Amazon subsidizing its brand from AWS revenues?

"Amazon's Antitrust Paradox"

Lina Khan

1989-

"[I consider] two potential regimes for addressing Amazon’s power: restoring traditional antitrust and competition policy principles or applying common carrier obligations and duties," (p.710).

Khan, Lina, 2017, "Amazon's Antitrust Paradox," Yale Law Journal 126(3):710-805

Search Engines

Consumers don't pay to search Google - enormous consumer welfare

- Google collects a lot of tracking information & data for advertisers

Google holds auctions to marketers to place advertisements on its results

Could Google be using its dominant market position to raise ad prices?

App Stores

Google and Apple app stores are dominant platforms

- Apple & Google do not charge the consumer anything for using the stores

- App developers set prices to consumers, Google & Apple take percentage of developers' sales

"Walled gardens" where users are locked-into Android or Apple ecosystem

App Stores

"The iPhone users argued that Apple’s 30% commission on sales through the App Store is an unfair use of monopoly power that results in inflated prices passed on to consumers.

Apple argued that only app developers, and not users, should be able to bring such a lawsuit. But the Supreme Court, in an opinion authored by Kavanaugh, rejected that claim."

Mergers: Is Facebook Buying Up its Potential Competitors?

Is New Antitrust Action Necessary?

Is New Antitrust Thinking Necessary?

Some Concluding Thoughts

But which are "good" and which are "bad"?

What is important in antitrust law?

- Protecting consumers? Protecting (some) businesses?

- Maximizing total economic surplus (Consumer surplus + producer surplus)?

What does market power look like/do?

- High prices, low output, low quality, few choice?

Some Concluding Thoughts